November 28, 2016

Kristi Maas, MD, ME, FACOG

Who me?

If you are reading this, chances are you are someone who may be interested in having children at some point in your life. You may not necessarily be at that point today- you may never reach that point- but don’t set this article aside; it is intended for you! Now is the best time inform yourself, consider your options, and take action if you want to!

Deciding when or if you want to get pregnant

As women we have competing interests with respect to our fertility. We desire to prevent pregnancy until a time we feel ready, but we also want to easily become pregnant when we are ready. The introduction of birth control pills in the 1950s and their widespread availability have allowed women to prevent unwanted pregnancies and better time a pregnancy for their life schedule. This trend, in combination with a shift towards women entering careers outside of the home, has resulted in women being older at the time of giving birth to their first child.

According to the Centers for Disease Control in 1970 the average age at first birth was 21.4 years and it increased to 25.8 years in 2012.[1] The rise reflects a six-fold increase in the number of first time mothers aged 35-39 and a four-fold increase among mothers 40-44 years old.[1]

With advancing age at first born, more women are faced with infertility. After many years of hiding these struggles due to fear or shame, patients with infertility are finally sharing their stories and the problem is well recognized. With this recognition comes a call for action. Women are motivated to prevent this difficult diagnosis.

How many eggs do you have and can you get more?

Our current understanding of female fertility is that a woman’s egg supply is a fixed pool of eggs that develop while a woman is still in her mother’s womb. This egg supply peaks at 6-7 million when she is approximately 20 weeks of gestation for her mother. The pool of eggs declines over time and at birth it is approximately 1-2 million.

A woman’s eggs remain in a resting state until she reaches puberty at which time she will start to develop multiple follicles with eggs every month. A primary follicle is selected from those that are developing and the other follicles die off. This primary follicle is the one from which a woman ovulates (releases a single egg). As a result, a woman uses up more than one egg per month despite generally only having one egg released and available to create a baby.

How does an egg become a baby?

When the egg is released from the ovary it is swept into the fallopian tube where it can meet with sperm to create an embryo. The embryo then travels down the fallopian tube and implants in the uterus. In an uncomplicated pregnancy, forty weeks later, a baby is born.

Why your age matters

If a woman is born with all of the eggs she will ever have and these eggs are lost over time it is clear that time and, therefore, age play an important role in fertility. In addition to a decreased supply, the remaining eggs from older women are more likely to be chromosomally abnormal as her age increases. Chromosomes contain genetic material that is passed from a parent to a child and chromosomally abnormal pregnancies are less likely to lead to a live birth. It is estimated that approximately 5% of a 25 year old woman’s eggs are chromosomally abnormal whereas 10-25% are abnormal among women in their thirties.[2,3,4,5] This number rises significantly to 50% or higher for women in their forties.[2,3,4,5] The increasing rate of abnormalities is due to the process of egg maturation and development prior to fertilization with sperm.

What can affect your ovaries and how well they work?

Genetic conditions such as Fragile X Syndrome and Turner’s Syndrome (45X0) are known to be associated with loss of egg number and quality at younger ages. Eggs can also be injured or prematurely depleted by treatments termed “gonadotoxic.” Gonadotoxic therapies include select medications such as chemotherapy, radiation, surgery to the ovaries or the blood supply to the ovary, or significant long-term health conditions.

When a woman faces a diagnosis of a serious chronic medical condition, cancer, or the need for gynecologic surgery she should be counseled about the reproductive risks of her disease and/or treatment. We know that radiation and chemotherapy are gonadotoxic, meaning they injure the ovaries and eggs, and that the effects depend upon the amount of the gonadotoxin and the age of the woman when she is treated. As a woman’s age at treatment increases relatively smaller doses of the gonadotoxin will result in a more significant loss of egg number and/or quality.

The treatment of pediatric, adolescent, and young adult cancers has become more effective and survivors have longer life expectancies. This underscores the need for discussion of the effects of therapy on fertility and the preservation of fertility prior to treatment.

Can we preserve fertility?

Previously, many women facing gonadotoxic therapy were given neither information nor the option to undergo fertility preservation. When the information was provided the only available method to preserve female fertility was to freeze embryos. This created a significant dilemma for single women, lesbians, bisexuals, or women not in a committed relationship with someone whom they can or would like to use their sperm to create embryos. The introduction of egg freezing now allows women to preserve their fertility independently.

The use and success of egg freezing in patients facing gonadotoxic therapies has opened the door to fertility preservation for women who desire to delay childbearing for personal or professional reasons. Many women find this an empowering option, allowing them to essentially stop their biological clock and taking the pressure off of creating a family “before it’s too late.”

How to choose when to preserve your fertility?

Regardless of the reason a woman decides to preserve her fertility, the best time to do it is now. It is clear that fertility declines with age and it is impossible to know how long a woman’s fertility will remain functional. Each woman’s fertile window- the time where she is able to become pregnant naturally- is different. The window is affected by multiple factors including health, family history, exposure to gonadotoxins, and even other currently unknown factors. At this time, closure a woman’s fertile window can’t reliably be predicted.

Can you find out how well your ovaries will respond?

Despite the inability to determine when a woman’s fertile window will close, testing can be done to predict how she will respond to medications used to stimulate her ovaries. These medications were initially used for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and are now being used for egg freezing, as well. The testing is called ovarian reserve testing and is generally done on day three of the menstrual cycle where day one is considered the first day of flow.

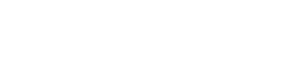

An ultrasound can be performed to look at the number of follicles within each ovary and calculate an antral follicle count- the total number of measurable follicles.

Blood can be drawn to test for follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol (E2), and anti-mullerian hormone (AMH). Follicle stimulating hormone is released from the brain and stimulates the ovary to develop follicles and the eggs within them. Estradiol is checked in conjunction with follicle stimulating hormone. It is produced from the ovary and it assists in the interpretation of follicle stimulating hormone levels. Anti-mullerian hormone is cycle independent, meaning that it can be checked at any time during the menstrual cycle. It is another marker used to estimate the pool of resting follicles within the ovary.

These tests are interpreted together to estimate a woman’s ovarian reserve. The tests do not predict a woman’s window of fertility nor is their utility in non-stimulated (IVF or egg freezing) settings fully understood at this time.

What is the preservation process like?

Patients who desire to have their eggs frozen will undergo a process called controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. This involves taking injectable medications on a daily basis to stimulate the ovaries to develop multiple follicles. The woman will be monitored with vaginal ultrasounds and blood tests until her developing follicles have grown adequately. At that time, the patient will be give herself a final injection, called the trigger shot, that helps prepare the eggs within the developing follicles for retrieval.

Approximately 36 hours after the trigger shot, the patient will have the eggs removed in a quick procedure and will be able to go home the same day. During the procedure, a physician uses ultrasound to find the woman’s ovaries and guides a needle into each developing follicle where the eggs are carefully removed. An embryologist identifies each egg, prepares it for freezing, and then freezes the egg. These eggs are frozen in time and will always reflect the woman’s age at the time they were frozen, not the age of the woman when it is thawed and used.

When a woman is ready to use her eggs, they are thawed, fertilized with sperm, and then transferred back into her uterus during a quick procedure called an embryo transfer.

Are there any long term effects of the process?

Research has shown that embryos created from egg donors where eggs are collected and frozen, then stored until desired use when they are thawed and fertilized, have equivalent outcomes to embryos from eggs that were not frozen prior to fertilization.[6] The potential of the frozen eggs to become a baby depends upon a woman’s age at the time of egg freezing, her ovarian reserve, and her health history. This will remain the same regardless of how long the eggs are frozen as they are essentially suspended in time.

The medications used have for egg freezing have been used for decades in the treatment of infertility with IVF and have not been shown to have long term risks. Additionally, babies born through IVF processes- which in most ways are the same as using frozen eggs- do not have an increased risk of birth defects or disorders above that that occurs with spontaneous pregnancies.

The egg freezing process does not decrease a woman’s egg supply. The medications she takes during the cycle rescue follicles that would otherwise die off when the primary follicle is selected and keep them alive to develop multiple useable eggs. The process does not steal eggs from future menstrual cycles.

Opinions from experts in the field

Increasing acceptance for egg freezing came in January of 2013 and January of 2014 when three well recognized fertility and OB/GYN societies (ASRM, SART, and ACOG) released statements that egg freezing should no longer be considered experimental.[7,8] The societies endorse the practice of egg freezing for patients undergoing gonadotoxic treatment.

They state that further evidence is required before recommending egg freezing specifically for use by patients who wish to electively defer childbearing as there is insufficient data to confirm its utility. This lack of data is primary a result of the newness of the technique and the small numbers of patients undergoing egg freezing previously.

Fertility preservation is catching on

Recently, egg freezing has become more mainstream in society, as well. Insurance companies are regularly covering the cost of fertility preservation for patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapies and now technological companies such as Facebook and Apple are paying for their employees to electively have their eggs frozen.

Some worry that this may be seen as encouraging women to delay childbearing and focus on their careers while others feel this is a liberating opportunity for women to uncouple reproduction from age. The long-term effects remain to be seen, but women who are interested should investigate the opportunity as well as their insurance coverage options.

As a woman in my 30’s who works in the field of reproductive endocrinology and who has seen the devastating impact of infertility I have chosen to electively freeze my eggs. I don’t now what the future holds for me, but I feel more secure knowing that I have placed my fertility on ice and not left it to chance.

References:

- Matthews, T and Hamilton, B. NCHS Data Brief No 152: First Births to Older Women Continue to Rise. May 2014.

- Sandalinas M, Marquez C, Munne S. Spectral karyotyping of fresh, non-inseminated oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod 2002;8:580-585.

- Pellestor F, Andreo B, Arnal F, Humaeu C, Demaille J. Maternal ageing and chromosomal abnormalities: new data drawn from in vitro unfertilized human oocytes. Hum Genet 2003;112:195-203.

- Fragouli E, Alfarawati S, Goodall NN, Sánchez-García JF, Colls P, Wells D. The cytogenetics of polar bodies: insights into female meiosis and the diagnosis of aneuploidy. Mol Hum Reprod 2011b;17:286-295.

- Fragouli E, Escalona A, Gutierrez-Mateo C, Tormasi S, Alfarawati S, Sepulveda S, Noriega L, Garcia J, Wells D, Munne S. Comparative genomic hybridization of oocytes and first polar bodies from young donors. RBM Online 2009;19:228-237.

- Sekhon et al. Frozen versus fresh donor egg IVF: similar efficacy and greater efficiency in a large donor egg IVF program. Fert Steril 2014;102(3):e83.

- ACOG: Committee Opinion No. 584: oocyte cryopreservation. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jan;123(1):221-2.

- Mature oocyte cryopreservation: a guideline. Practice Committees of American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:37-43.

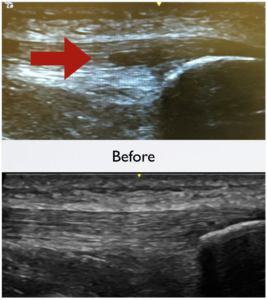

The patellar tendon is healed 3 months after treatment with Lipogems®.

The patellar tendon is healed 3 months after treatment with Lipogems®.